Micro

Micro

Micro architecture & design patterns for microservices

We’ve had a lot of questions about the micro architecture and design patterns for microservices over the past few months. So today we’ll try cover both.

About Micro

Micro is a microservices toolkit. It was built to be opinionated in it’s features and interfaces while providing a powerful pluggable architecture allowing the underlying dependencies to be swapped out.

Micro is focused on addressing the fundamental requirements for building microservices and has looked to do this by taking a thoughtful and measured approach to it’s design.

If you would like to read up on the Micro toolkit check out the previous blog post here or if you would like to learn more about the concept of microservices look here.

We’ll quickly recap on the features of Micro before delving into further architecture discussion.

The Toolkit

Go Micro is a pluggable RPC framework for writing microservices in Go. It provides libraries for service discovery, client side load balancing, encoding, synchronous and asynchronous communication.

Micro API is an API Gateway that serves HTTP and routes requests to appropriate micro services. It acts as a single entry point and can either be used as a reverse proxy or translate HTTP requests to RPC.

Micro Web is a web dashboard and reverse proxy for micro web applications. We believe that web apps should be built as microservices and therefore treated as a first class citizen in a microservice world. It behaves much the like the API reverse proxy but also includes support for web sockets.

Micro Sidecar provides all the features of go-micro as a HTTP service. While we love Go and believe it’s a great language to build microservices, you may also want to use other languages, so the Sidecar provides a way to integrate your other apps into the Micro world.

Micro CLI is a straight forward command line interface to interact with your micro services. It also allows you to leverage the Sidecar as a proxy where you may not want to directly connect to the service registry.

That’s the quick recap. Now let’s go deeper.

RPC, REST, Proto…

So the first thing you might be thinking is why RPC, why not REST? Our belief is that RPC is a more appropriate choice for inter-service communication. Or more specifically RPC using protobuf encoding and APIs defined with protobuf IDL. This combination allows the creation of strongly defined API interfaces and an efficient message encoding format on the wire. RPC is a straight forward, no frills, protocol for communication.

We’re not alone in this belief.

Google is creator protobuf, uses RPC internally and more recently open sourced gRPC, an RPC framework. Hailo was also a strong advocate of RPC/Protobuf and benefited tremendously, interestingly more so in cross team development than systems performance. Uber choosing their own path has gone on to develop a framing protocol for RPC called TChannel.

Personally we think the APIs of the future will be built using RPC because of their well defined structured format, propensity for use with efficient encoding protocols such as protobuf with the combination offering strongly defined APIs and performant communication.

HTTP to RPC, API…

In reality though, we’re a long way from RPC on the web. While its perfect inside the datacenter, serving public facing traffic e.g websites and mobile APIs, is a whole other deal. Let’s face it, it’s going to be a while before we move away from HTTP. This is one of the reasons why micro includes an API gateway, to serve and translate HTTP requests.

The API gateway is a pattern used for microservice architectures. It acts as a single entry point for the outside world and routes to an appropriate service based on the request. This allows a HTTP API itself to be composed of different microservices.

This is a powerful architecture pattern. Gone are the days where a single change to one part of your API could bring down the entire monolith.

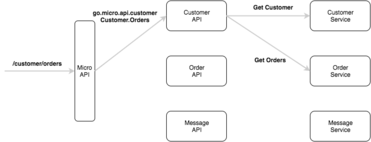

The micro API uses path-to-service resolution so that each unique request path can be served by a different API micro service e.g. /user => user api, /order => order api.

Here’s an example. A request to /customer/orders will be sent to the API service go.micro.api.customer with method Customer.Orders.

You might be wondering what the heck an API service is. Now is about the right time to discuss the different types of services.

Types of Services

The concept of Microservices is all about separation of concerns and borrows a lot from the unix philosophy of doing one thing and doing it well. Partly for that reason we think there needs to be a logical and architectural separation between services with differing responsibilities.

I’ll acknowledge right now that these concepts are nothing new but they are compelling given they’ve been proven in very large successful technology companies. Our goals are to spread these development philosophies and guide design decisions via tooling.

So here’s the types of services we currently define.

API - Served by the micro api, an API service sits at the edge of your infrastructure, most likely serving public facing traffic and your mobile or web apps. You can either build it with HTTP handlers and run the micro api in reverse proxy mode or by default handle a specific RPC API request response format which can be found here.

Web - Served by the micro web, a Web service focuses on serving html content and dashboards. The micro web reverse proxies HTTP and WebSockets. These are the only protocols supported for the moment but that may be extended in the future. As mentioned before, we believe in web apps as microservices.

SRV - These are backend RPC based services. They’re primarily focused on providing the core functionality for your system and are most likely not be public facing. You can still access them via the micro api or web using the /rpc endpoint if you like but it’s more likely API, Web and other SRV services use the go-micro client to call them directly.

Based on past experiences we’ve found this type of architecture pattern to be extremely powerful and seen it scale to many hundreds of services. By building it into the Micro architecture we feel it provides a great foundation for microservice development.

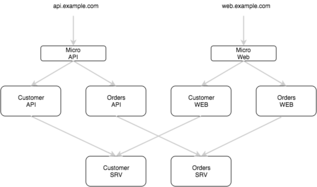

Namespacing

So you might wonder, what’s to stop the micro api from talking to web services or the micro web talking to api services. We use logical namespacing to separate these. By prefixing a namespace to a service name we clearly identify it’s purpose and place in the system. It’s a simple but effective pattern that has served us well.

The micro api and web will compose a service name of the namespace and first path of a request path e.g. request to api /customer becomes go.micro.api.customer.

The default namespaces are:

- API - go.micro.api

- Web - go.micro.web

- SRV - go.micro.srv

You should set these to your domain e.g com.example.{api, web, srv}. The micro api and micro web can be configured at runtime to route to your namespace.

Sync vs Async

You’ll often hear microservices in the same sentence as reactive patterns. For many, microservices is about creating event driven architectures and designing services that interact primarily through asynchronous communication.

Micro treats asynchronous communication as a first class citizen and a fundamental building block for microservices. Communicating events through asynchronous messaging allows anyone to consume and act upon them. New standalone services can be built without any modification to other aspects of the system. It’s a powerful design pattern and for this reason we’ve included the Broker interface in go-micro.

Synchronous and asynchronous communication are addressed as separate requirements in Micro. The Transport interface is used to create a point to point connection between services. The go-micro client and server build upon the transport to perform request-response RPC and provide the capability of bidirectional streaming.

Both patterns of communication should be used when building systems but it’s key to understand when and where each is appropriate. In a lot of cases there’s not right or wrong but instead certain tradeoffs will be made.

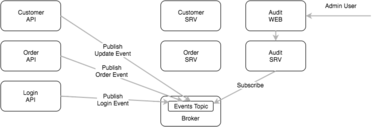

An example of where the broker and asynchronous communication could potentially be used is in an audit trail system for keeping track of customer event history.

In this example every API or service publishes an event when some action occurs such as a customer logs in, update their profile or places an order. The audit service will subscribe for these events and store them in a time series database of some kind. An admin or anyone else can then view the history of events that have taken place within the system for any user.

If this was done as a synchronous call we could easily overwhelm the audit service when there’s high traffic or as the number of bespoke services increases. If the audit service was taken offline for some reason or a call failed we would essentially lose this history. By publishing these events to the broker we can persist them asynchronously. This is a common pattern in event driven architectures and for microservices.

OK wait, brief pause, but what defines a microservice?

We’re covering a lot of what the Micro toolkit provides for microservices and we’ve defined the types of services (API, WEB, SRV) but there’s nothing really about what a microservice actually is.

How does it differ from any other kind of application? What gives it this special name of a “microservice”.

There’s varying definitions and interpretations but here’s a couple that fit best in the Micro world.

Loosely coupled service oriented architecture with a bounded context

Adrian Cockcroft

An approach to developing a single application as a suite of small services, each running in its own process and communicating with lightweight mechanisms

Martin Fowler

And because we love the unix philosophy and feel it fits perfectly with the microservice philosophy.

Do one thing and do it well

Doug McIlroy

Our belief and the idea we build on is that a microservice is an application focused on a single type of entity or domain, which it provides access to via a strongly defined API.

Let’s use a real world example such as a social network.

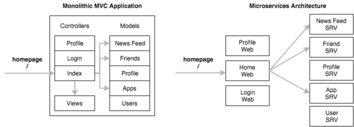

A well defined software architecture pattern that became popular with the rise of Ruby on Rails was MVC - Model-View-Controller.

In the MVC world each entity or domain would be represented a model which in turn abstracts away the database. The model may have relationships with other models such as one to many or many to many. The controller processes in coming requests, retrieves data from the models and passes it to the view to be rendered to the user.

Now take the same example as a microservice architecture. Each of these models is instead a service and delivers its data through an API. User requests, data gathering and rendering is handled by a number of different web services.

Each service has a single focus. When we want to add new features or entities we can simply change the one service concerned with that feature or write a new service. This separation of concerns provides a pattern for scalable software development.

Now back to our regularly scheduled program.

Versioning

Versioning is an important part of developing real world software. In the microservice world it’s critical given the API and business logic is split across many different services. For this reason its important that service versioning be part of the core tooling, allowing finer grained control over updates and traffic shaping.

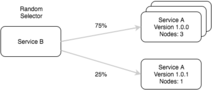

In go-micro a service is defined with a Name and Version. The Registry returns a service as a list, splitting the nodes by the version they were registered with.

This is our building block for version based routing.

type Service struct {

Name string

Version string

Metadata map[string]string

Endpoints []*Endpoint

Nodes []*Node

}

This in combination with the Selector, a client side load balancer, within go-micro ensures that requests are distributed across versions accordingly.

The selector is a powerful interface which we’re building on to provide different types of routing algorithms; random (default), round robin, label based, latency based, etc.

By using the default random hashed load balancing algorithm and gradually adding instances of a new service version you can perform blue-green deployment and do canary testing.

In the future we’ll look to implement a global service load balancer which ties into the selector allowing for routing decisions based on historic trends within a running system. It will also be capable of adjusting the percentage of traffic sent to each version of a service at runtime and dynamically adding metadata or labels to a service, which label based routing decisions can be made on.

Scaling

The above commentary on versioning begins to hint at the foundational patterns for scaling a service. While the registry is used as a mechanism for storing information about a service, we separate the concern of routing and load balancing using the selector.

Again the notion of separation of concerns and doing one thing well. Scaling infrastructure as well as code is very much about simplicity, strongly defined APIs and a layered architecture. By creating these building blocks we allow ourselves to construct more scalable software and address higher level concerns elsewhere.

This is something fundamental to the way Micro is written and how we hope to guide software development in a microservices world.

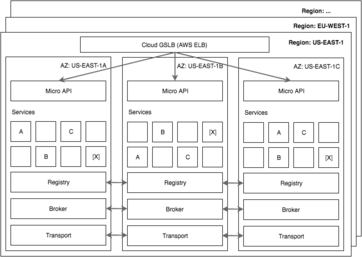

We’ve briefly discussed cloud architecture patterns in a previous post about Micro on NATS and will re-address some of the ideas here.

When deploying services in a production setting you’ll be looking to build something scalable, fault tolerant and performant. Cloud computing now gives us access to pretty much unlimited scale but nothing is impervious to failure. In fact failure is one of the key aspects that we look to address when building distributed systems and you should take this into consideration when building your infrastructure.

In the world of the cloud, we want to be tolerant of Availability Zone (datacenter) failures and even entire Region (Multi DC) outages. In past days, we used to talk about warm and cold standby systems or disaster recovery plans. Today the most advanced technology companies operate in a global manner, where multiple copies of every application is running in a number datacenters across the world.

We need to learn from the likes of Google, Facebook, Netflix and Twitter. We must build systems capable of tolerating an AZ failure without any impact on the user and in most cases dealing with region failures within minutes or less.

Micro enables you to build this kind of architecture. By providing pluggable interfaces we can leverage the most appropriate distributed systems for each requirement of the micro toolkit.

Service discovery and the registry are the building block of Micro. It can be used to isolate and discover a set of services within an AZ or Region or any configuration you so choose. The Micro API can then be used to route and balance a number of services and their instances within that topology.

Summary

Hopefully this blog post provides clarity on the architecture of Micro and how it enables scalable design patterns for microservices.

Microservices is first and foremost about software design patterns. We can enable certain foundational patterns through tooling while providing flexibility for other patterns to emerge or be used.

Because Micro is a pluggable architecture it’s a powerful enabler of a variety of design patterns and can be appropriately used in many scenarios. For example if you’re building video streaming infrastructure you may opt for the HTTP transport for point to point communication. If you are not latency sensitive then you may choose a transport plugin such as NATS or RabbitMQ instead.

The future of software development with a tool such as Micro is very exciting.

If you want to learn more about the services we offer or microservices, check out the blog, the website micro.mu or the github repo.

Follow us on Twitter at @MicroHQ or join the Slack community here.